In my previous article, I promised to go deeper into how money evolved throughout history. We will do a simple overview of that and more importantly, focus on why they’ve been replaced.

As a reminder, here are the basic properties that good money should have:

Scarcity: Is it limited in supply?

Divisibility: Can the money be divided into smaller units?

Portability: Can it be easily transported?

Durability: Can it withstand wear and tear?

Fungibility: Is one unit of that money exactly the same as another?

Verifiability: Can it be easily identified as genuine?

To understand how money will continue to evolve, it is helpful to understand the history of money. Lets go through this topic in five sections:

Primitive Forms of Money

The Emergence of Gold

Improvements That Led to The Gold Standard

The Collapse of The Gold Standard

The Current State of the Global Financial System

1. Primitive Forms of Money

Before the invention of metal coins, money was fragmented and highly local. Different communities and regions had their own local currencies. For example, a population with less than 500 people on an island can decide to use a form of handcrafted seashell as their own local currency.

As economies grew and technology advanced, more standardized forms of money were needed to facilitate trades and transactions. Hence, early humans looked for different objects to use as money, ranging from seashells to stones to tobacco.

Obviously, we no longer use these primitive forms of money. But it is important to understand why our ancestors collectively decided to abandon them.

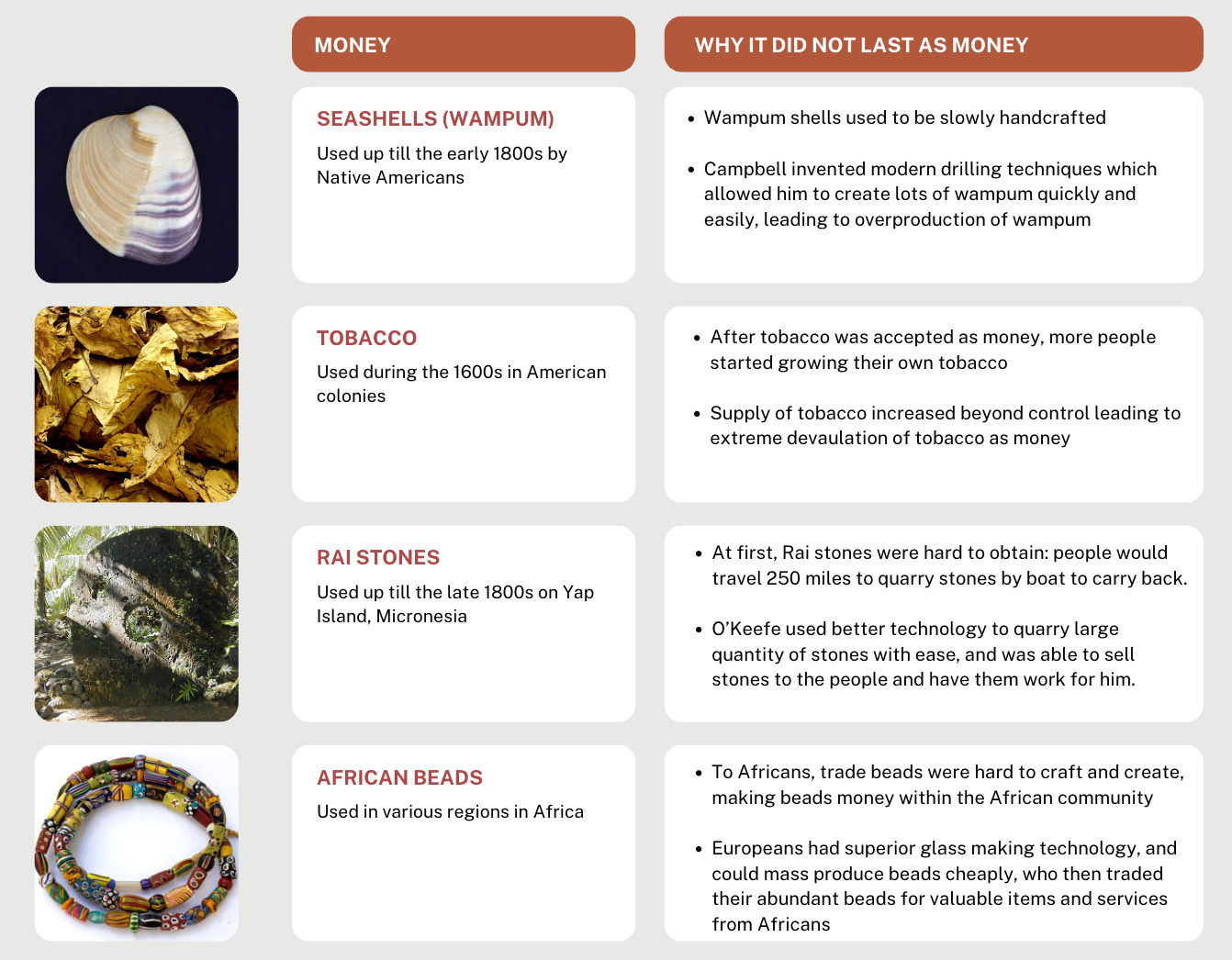

Simply put, older forms of money failed because they couldn’t meet the properties that define “good” money. Here are some examples of primitive forms of money that are no longer commonly accepted.

There are two key lessons here:

Firstly, scarcity is the most important factor that decides whether money is useful. Primitive forms of money were made obsolete because technological advancements enabled small groups of people to increase the supply of that money substantially, allowing that group of people to amass wealth directly and disproportionately. While primitive forms of money all suffered from issues of fungibility, verifiability, divisibility etc., the main reason we did not continue to use them as money is the lack of scarcity due to improvement in technology that allowed other people to mass produce them.

Secondly, commodities with high utility value (e.g. tobacco, cocoa) are not good forms of money. If something is deemed as money, you would naturally be incentivized to hoard it. If something with high utility becomes money, the result is people start to hoard these items, which restricts access and drives up the prices of these commodities. Humans are smart enough to realize that this does not work in the long term, hence we have naturally converged to using things that have little to no utility as money.

2. The Emergence of Gold

What made gold universally valuable? Gold performs decently well across most dimensions of the properties of money. Gold is relatively divisible, durable, relatively fungible, and most importantly, scarce.

Typically, if an object has deemed as money, people are incentivized to create, earn and store more of it. This is why people found ways to produce more of shell money or tobacco or beads to make themselves more wealthy.

However, gold has been able to resist that for thousands of years. No matter how much technology has advanced, we historically cannot increase the supply of gold by more than 2% per year, typically averaging around 1.5% per year.

Gold is also a commodity that has little utility value. Only roughly 6% of all gold is used for electronics purposes, and the other 93-94% is either in the form of jewellery or bullions (pure gold bars or coins). In other words, people hoard gold in one of those two forms.

Another quantitative way of explaining gold’s emergence as money is the stock-to-flow ratio.

Stock: The total amount of a available resource that exists above ground (in circulation).

Flow: The new supply of that resource added each year (through mining in the case of gold and silver).

In general, a high stock-to-flow ratio is a prerequisite for strong money. This means that there is enough available money for everyone to use it (high stock), while the new money added to the system is small relative to the overall stock (low flow).

In her book Broken Money, Lyn Alden explains the significance of the stock-to-flow ratio:

After thousands of years, two commodities beat all the others in terms of their monetary attritibutes: gold and silver. Only they were able to retain a high enough stock-to-flow ratio to serve as money, despite civilizations constantly improving their technological capabilities throughout the world.

Gold has averaged a stock-to-flow ratio of 50 or above throughout history; silver generally has a stock-to-flow ratio of 10 or more, while most other commodities have a stock-to-flow ratio that is below 1 or 2, even for rare elements like platinum or rhodium.

The stock-to-flow ratio also helps explains why other commodities used as primitive forms of money mentioned above all got replaced or failed; people eventually created more of the commodity, thereby increasing the supply (flow) enough to meaningfully reduce its stock-to-flow ratio, such as with shells, tobacco, or beads.

Other rare metals such as platinum, iridium, palladium are also scarce, but they are not used as money. Some of them are actually rarer than gold or silver (less available quantity in nature, harder to extract etc.), and they have much more utility value in industrial applications. Hence, no matter how much people increase the supply (flow) of these rare metals, they are rapidly consumed in industrial applications, reducing the availability (stock) of these metals. The effect is a low stock-to-flow ratio for these metals. Again, items with high utility value do not make good money.

Why don’t we use gold for day-to-day transactions?

If gold is such a great form of money, why don’t we use it on a daily basis? Practically speaking, gold does not perform as well across certain properties of money, especially on divisibility. You can only properly cut gold up to a certain weight before it is too difficult to divide it further. Imagine the following problems if you want to pay for something in gold:

How do you physically cut or divide the gold? With metal cutters? Machines? Are you strong enough to operate those tools?

How do you measure the weight of gold accurately? Do all shops need a weighing machine? What if the weighing machine is not accurate? Do you bring your own machine?

How do you match the price of whatever you are paying for if the price is less than 0.1 grams of gold?

There are all sorts of limitations when it comes to gold’s divisibility, and this also explains why you are not paying for your restaurant meal or groceries with physical gold. You cannot be bringing a 1 gram or 0.1 gram gold coin around with you and accurately divide that gold to its market value to pay for your meal or groceries.

Today, gold can still be used for larger payments if both the buyer and seller agrees to the terms, or among industry merchants. When I was in the retail gold industry, I saw how factory workers have to manually cut large physical gold bars for payment purposes (either for wages or payments to other merchants), and they would use large steel bolt cutters or machines like this to cut the gold bars. They often have to carefully recut smaller pieces to match the weight they are trying to achieve. Not very user-friendly for the majority of the population.

Gold also faces certain limitations when it comes to portability, fungibility and verifiability.

Portability: Even if you are tremendously wealthy and own a huge amount of physical gold, it is tough to carry that heavy bulk of gold with you around.

Fungibility: Gold products can have different purities, hence one gold bar is not necessarily the same as another.

Verifiability: Societies tried to workaround the fungibility issue by establishing official certifications for gold bars under that are approved by either governments or gold associations. However, it is still possible for people to counterfeit gold, which increases the cost and difficulty in verifying gold. Even with established certification and detection methods, counterfeit gold is still a prevalent issue in recent years.

However, because gold managed to maintain its scarcity property, it is still a popular form of savings. For all its shortcomings, gold is deemed valuable because it is scarce.

3. Improvements That Led to The Gold Standard

Nevertheless, people still needed ways to trade and transact reliably and efficiently. There is a lot of history in how societies improved money that cannot be covered in a short article, but the progression to the Gold Standard roughly occurred in the following stages:

Civilizations gravitated towards gold and silver as a sound form of money as they are the only resources to not be oversupplied by improvements in technology.

Metal coins based on gold or silver were issued by central entities (kingdoms, empires or governments) to use as official currencies to facilitate trading and all other economic activities.

Improvements in banking systems reduced the need for metal coins and improved gold’s limitations on its divisibility and portability.

Banks allowed people to store their physical gold and issue paper credits that allows people to redeem gold based on how much paper credits they have. For example, you might deposit 1 gram of gold and receive 1 piece of the paper credit. You can then use this 1 piece of paper to transact with other people.

These paper credits were effectively the second layer that represented gold, thereby indirectly increasing gold’s divisibility. For example, instead of 1 paper for 1 gram of gold, you could have 10 paper credits represent 1 gram of gold.

The gold-backed paper credits system made gold effectively more divisible and portable compared to physical gold.

As banks realized that most people do not redeem gold all at once, they issued more claims than the gold they physically stored, beginning the fractional reserve banking system

For example, if 1 paper represented 1 gram of gold, and the bank only held 1000 grams of gold, they should have been only able to issue 1000 pieces of paper. Instead, they would issue 1100 paper credits worth up to 1100 grams of gold.

Fractional reserve banking is still used by all conventional banks today. It literally means the banks only hold a “fraction” of their real reserves compared to the paper credits they issued.

To improve efficiency, banks consolidated into central banks by specific countries or regions, which issued nationwide paper slips that allowed people to claim specific amounts of gold. This is commonly known as the Gold Standard. Individual banks managed these paper slips and the storage of gold based on a preset rule by the central bank.

Take note on the fractional banking system and the consolidation of power by central banks who can issue more paper credit (paper money) at their discretion. These are important points that we will revisit later.

4. The Collapse of The Gold Standard

During the first world war, almost all countries suspended the gold standard, meaning people could no longer redeem their gold with the paper credit they held.

For example, Germany suspended the gold standard when the first world war broke out in 1914. Germany then issued a lot more paper credit than the gold they actually held, with nothing tangible to back up all the paper credits they issued. As Germany lost the war, the paper credits were greatly devalued and led to the hyperinflation of the German Papiermark (called Marks) between 1921 to 1923. Hyperinflation was so severe that a loaf of bread in Berlin that cost around 160 Marks at the end of 1922 cost 200,000,000,000 Marks by late 1923.

Essentially, the German Papiermark collapsed because it lost its scarcity property. This is called currency debasement.

Fast forward to the 1940s. The war was over, and the US, representing a majority of the world economy at that time, emerged as the global leader and successfully pushed for the Bretton Wood System in 1944.

Under this system, all non-US currencies would be tied to the US Dollar, while only the US Dollar would be backed by (or pegged to) gold. Countries could claim gold by requesting for gold through the US.

This system worked fine for a few years, but similar to all countries before it, the US started printing more money (issuing more paper credit) than the amount of gold they held, reducing the value of US Dollar.

Foreign countries aggressively exchanged money for gold through the US, causing the US gold reserves to drop by half by 1970, further reducing the value of the US dollar that is supposedly backed by gold.

Eventually, this “run” on the US dollar, where foreign countries would sell the US dollar in exchange for gold, forced the suspension of the redeemability of US dollar to gold in 1971, effectively ending the Bretton Wood System.

5. The Current State of The Global Financial System

Today, our dominant form of money (called fiat money) is not backed by anything tangible. It is a shared delusion; pieces of paper or numbers that people collectively agree to represent a store of their wealth and financial energy.

However, as history has shown, good money should have actual scarcity, and people generally will find the most scarce form of money to hoard. Today’s system forces people to actually invest their fiat money in risky assets or equities in order to catch up to inflation, while risking potential losses in those investments. The alternative, where you simply keep your money in the bank, means that money becomes more worthless overtime due to ever rising money supply which leads to inflation.

You could argue that Fixed Deposits or Money Markets are “safe” options with stable returns, but there is no guarantee that these returns allow you to conserve your wealth (by offering returns higher than real inflation), and especially not if there are drastic changes in government policies that lead to massive inflation and reduction of your wealth, like what policies enacted during COVID resulted in.

If you think the trippling of the US money supply from ~$180 billion to ~$600 billion in 1950-1970 mentioned above is bad, here is a reminder of where we are today.

The current fiat money breaks the most important property of money: scarcity. It is a horrible store of value as its supply can be increased at a whim, putting your hard earned money at risk.

But the System Still Works Today

At this point, some might point out that the world has advanced so much since the 1970s despite all the problems mentioned above.

I would rephrase it and say that society managed to advanced so much despite all the problems with our money system.

In his essay and book on the Changing World Order, Ray Dalio states:

When wealth and values gaps are large and there is an economic downturn, it is likely that there will be a lot of conflict about how to divide the pie.

In other words, a system that promotes an ever increasing wealth gap by debasing the currency, resulting in ever increasing cost of living for essentials such as food, shelter and energy, will likely result in conflict.

Furthermore, people often don’t realize how bad the problem is until it is too late. For example, the Roman empire continuously debased its currency for 500-600 years, until the economy was paralyzed from hyperinflation, soaring taxes, and worthless money, which played an important role in the eventual political turmoil and collapse of the Roman empire.

Not to mention, the fiat system has not worked well for most people living in countries that underwent hyperinflation in recent years such as Lebanon, Turkey, and Egypt.

Conclusion

History has shown that humans will either earn or create more of the things that people consider as money to enrich themselves. This is necessary for our survival. Most people do this by creating value in society and then get rewarded by others. Some do it by creating more of the money without much effort. The ability to create money endlessly is enabled by the fractional banking system and the power held by central banks (and by extension, the politicians in most countries).

“Give me control of a nation’s money supply, and I care not who makes its laws.”

Mayer Amschel Rothschild

The current system’s design where fiat money can be indefinitely increased in its supply is similar to how O’Keefe was able to extract more Rai stones easily to exploit the Yapese, or how the Europeans learnt how to mass produce African beads to trade for useful goods or services cheaply.

But what if we have something that is better than gold or fiat money? Something that is more scarce, divisible, durable, portable, fungible, and verifiable? Furthermore, something that is politically neutral like gold?

That something is already here. Study Bitcoin.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this publication is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Readers are encouraged to do their own research and consult with a licensed financial advisor before making any investment decisions.